The Ice Cream Truck Cometh

Jeff Zimmermann's faithful

paintings of ice cream trucks

ring the chimes of memory.

By Jeff Huebner

Artist Jeff Zimmermann has bittersweet memories of ice cream trucks. He recalls hearing the faraway jingle of the bells as a little kid growing up in Westchester, running inside the house to ask his parents for change, and then coming back outside to stand in line. He remembers the summer sun, the trees and the lawns, the enticing colors of the treats painted on the sides of the truck. Zimmermann-who usually bought frozen bubble gum- also recalls how prankish teenagers would distract the vendors long enough so one of them could climb behind the wheel and drive the truck down the block. He and the other kids would sit on the curb laughing.

"The driver would get all pissed off," Zimmermann says. "After a while, if there were any older, bigger kids on the block, the guy wouldn't stop-he'd try to blow right past us. But the trucks couldn't go very fast, and we could run fast enough to keep up with it...Eventually, they wouldn't come to our block."

Zimmermann, who's 30, graduated with a graphic arts degree from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign in 1992. After college, he joined the Jesuit Volunteer Corps and for the next three years was a social worker dealing with street kids in Tacna, Peru, a shantytown. Back in the U.S. and wanting to be an artist, he moved to Chicago, took a painting class at Columbia College, and taught continuing education course at the School of the Art Institute. The latter connection led, in 1996, to a teaching job at Casa Juan Diego, a Pilsen youth center run by Saint Pius V parish. Working with the teens there, Zimmermann painted his first outdoor mural, Eduacacion: See y Know, on the wall of the center.

This led to other parish-sponsored works, like Unbelievable the Things You See, at 1858 S. Ashland, a depiction of a Mexican family crossing the Rio Grande led by the Virgin of Guadalupe and last year's epic Familiar, which he worked on for two years. Sited on the side of the Saint Jude Gift Shop at the southwest corner of 19th and Ashland, the 2,500-square-foot artwork–the largest and most prominent mural in Pilsen–shows Mexican-American families in conflict and in harmony; its images are based on photos that Zimmermann took during parenting workshops sponsored by the parish.In the last four years, working on his own, he has also painted quirky, community-oriented murals at North and Honore, Chicago and Milwaukee, and Ashland and Carroll.

Zimmermann didn't start thinking about ice cream until a year ago, when he painted a large, realistic acrylic on canvas of a blue Fountain Fair truck –"The Ice Cream Parlor on Wheels"– based on a photograph he had taken. He sold the piece out of his studio, and then did another one very similar to it. "It came to me that I love these things, and I didn't want to paint just one," he says. "If you hang just one, it's cute–it doesn't evoke any ideas. Everyone can identify with ice cream trucks, bring some memory and emotion to them. You hear the jingle of a bell and have a feeling, like remembering the summer, or Mr. Johnson's or Mr. Ahmed's smiling face. People love them for theat, and can relate to that."

Yet, Zimmermann adds, "If you had a number of trucks together, maybe collectively they'd make you think about how you're remembering them. Then they'd be about the truck, the object, not the experience. They're a piece of machinery with dents and flaws and scratches–like the modern reality of our memories and there's chicken wire on them now. Everyone immediately associates them with being happy objects, and I wanted to challenge that notion."

So last spring Zimmermann began "stalking" ice cream trucks, getting deeper and deeper into the world of mobile ice cream vending. For four months he took photographs of trucks and pushcarts in his Bucktown neighborhood and in Pilsen, where, he says, vendors were more numerous.

"Whenever I heard a jingle I looked for an ice cream truck," Zimmermann, says. "I'd follow it around and stare at it. I'd watch products leave the truck and watch kids jam ice cream in their faces. I would always buy ice cream as a way to approach the guys and get pictures, and I don't even eat ice cream. The truck drivers thought it was silly–'Why? O.K., if you're really serious.' One guy got really mad. 'No pictures! Get away from my truck!'"

Zimmermann even went out to the Pars Ice Cream lot at Arthington and Cicero, where he was astounded to see "hundreds of trucks and a graveyard of junkers." It was there he made a prize discovery. He told a mechanic that their trucks weren't the type he remembered from when he was a kid. "I described it to him, and he said there were only a couple of those left," Zimmermann says. "He brought me out and showed me one parked in the back." It was the same white Good Humor truck he recalled from his suburban childhood, the kind where the driver must exit through and exposed passenger door to retrieve ice cream from a side freezer.

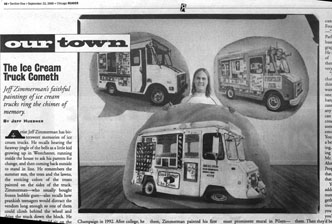

Zimmermann eventually focused on six trucks "with a lot of character, " amassing dozens of photographs. For the most part, he says, they were "clean shots" of just the trucks themselves all from the same side angle. The paintings are devoid of drivers and lines of kids and they lack any identifying surroundings. Stripped of context, they are oddly forlorn, charged with a surreal presence. Painted on grommeted, roughly elliptical canvases about six feet across, the trucks seem to float in midair, as if conjured from memory. Yet they have been faithfully rendered, their surfaces meticulously festooned with a colorful array or treats like ice cram cones, sandwiches, sundaes, crunch bars, Drumsticks, and popsicles.

He didn't stop there. He painted ice cream trucks on smaller canvases, and did drawing of pushcart vendors. He collected ice cream wrappers, finding that many "frozen confections" –as some products were labeled–contained candy centers and gum balls, their wrappers adorned with cartoon characters such as Pokemaon, Power Rangers, Super Mario Brothers, Bugs Bunny, and Tweety.

"I'd be looking for unique wrappers I didn't have," Zimmermann says. "Just like the kids, I'm buying it for the cool package, not knowing what's inside of them." He painted images of vendors, trucks, and kids on the wrappers. He also did a series of works on masonite panels using ice cream bars as a medium–and was surprised to discover that after the stuff melted it left a goopy oily residue that would never quite dry.

Zimmermann rarely exhibits his studio work, choosing instead "to build up my artistic credibility on the street rather than in galleries." At some point, he says, "I realized that no one was ever going to see my paintings, so I decided to do paintings where everyone was going to have to see them. You can put a message out there, you can say something. It's there for everyone to see–and it's free."

Zimmermann's paintings of ice cream trucks and his other frozen-confection-related works, however, are going to cost you.

The Chicago Reader, September 22, 2000